🎙 Interview with Steven Yau

Today, we welcome Steven Yau (aka. yaustar), a game developer with over 15 years of experience in the games industry ranging from AAA console games to XR and F2P mobile games. Steven has worked for companies like EA, King and PlayCanvas at Snapchat.

Thank you, Steven, for taking the time to answer some questions for WebGameDev.com. I look forward to learning from your experience what working in this industry professionally is like! Could you introduce yourself and tell us about some key moments of your career?

Hi everyone 👋! As mentioned above, I’ve been working in games or games-related industries for a while now. I love to tinker and find interesting ways to use technologies in playful ways.

Ooo, key moments. Definitely getting my first ‘real’ job in games at EA way back in 2006 comes top of the list as that kicked off my whole career. I was lucky to be in a very supportive team who would mentor me across multiple projects.

Getting that role did require some luck though, I struggled a lot with the programming tests at the time and EA was no exception with me failing the graduate programmer interview.

But luckily the recruiter called me back for a contract Level Scripting role on the Harry Potter movie series. It paid less but it was a great entry on my CV. AAA, big IP and with a well known developer. I also managed to impress the team during that project as I was offered a full time Software Engineer role at the end of the contract!

Working at Playfish is another highlight. It was a high energy and creative place to work and an incredible sociable culture. I’m not sure that I could keep up in my 40s but during my late 20s, it was such a fun place to work at. The studio is no longer around but people have since created/started up successful games studios including Space Ape, Trailmax and Super Solid.

And lastly, joining the PlayCanvas team again at Snapchat. It has been incredible to work with a very talented team that’s so intrinsically driven. Additionally, we were given huge autonomy by Snap which was a huge empowerment to the team. It’s rare to have an opportunity where you could be working on game related technology, at a ‘big tech’ company and have such freedom as a team.

What are some of the games you’ve enjoyed working on the most? What are some of your proudest “I made this” moments?

I’ve been incredibly lucky to work on so many games throughout my career. AAA games normally take years to release but working on film IP titles meant that there was a fixed schedule (for better or for worse!).

Seeing my first game, Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix on store shelves was a very historic moment for me. But it was my second game, Harry Potter and the Half Blood Prince where I was a Gameplay Engineer that I felt, ‘yeah, I made this’ for the first time!

Under some great mentorship from my line manager and support from the team, I was given ownership of a key gameplay pillar: potion making.

With Wii as our lead platform, there was focus on making the motion controls feel awesome’ to our young audience demographic. I went through many iterations of the controls, user testing, changing sensitivity curves, etc until we felt it was ‘right’. I still vividly remember the progression stages of the minigame, from where it started as a clumsy, third person, spellcasting experience to the 1st person, responsive and immersive experience it finished as.

From the GamesRadar Wii Review:

Let’s start with potions, as it’s the Big New Thing in Half-Blood Prince. It’s brilliant. … Not having ever made a potion we can’t judge how accurate it all is, but the gestures are spot-on and fun to perform - it’s a truly great mini game.

Can’t get much better feedback than that! (and it is still fondly remembered today)

There was so much I learned through that project around creating an interactive experience including:

- The importance of short iteration and feedback loops.

- Identifying and focusing on the core and building outwards in baby steps.

- Hacking to get to the fun quickly.

I’m very grateful that I got those lessons early on in my career. Other games or projects that also gave me that ‘I made this’ feeling include:

- Restaurant City (Playfish) - Lots of my friends were playing this on Facebook so there was some extra meaning for the features and content I was adding to the game.

- Farm Heroes Super Saga (King) - I was on that project from concept, pitching and production for King’s second largest IP. To get that released to an audience of that size was hugely rewarding. Especially when you see it being played in public!

- WebVR Labs (PlayCanvas) - Super proud to have this as a showcase demo of a historic event when Google released WebVR API in Chrome 58.

For people outside the game industry, what are the main differences between typical web development jobs and making games for big game studios like EA or King?

I’ve never had a typical web development job myself, so I can’t really answer that one 😅. I’ve personally found that working in games varies a lot in itself, depending on the studio team and game. Especially when it comes to things like team culture, team size or game type.

Generally, I found that larger teams, as an individual, tend to have deeper focus on one part of the game that you are responsible for and iterate on and improve. It is also likely to be part of a smaller cross-discipline team working on that area. For example, you may be a gameplay programmer working on weapon mechanics, working with a designer who helps with balancing, and/or an artist to work on the visuals, the models, the animations, etc. That’s the kind of thing you’d be concentrating on throughout the whole development cycle. Maybe you have some different areas to work on, but generally you’d be known as and the ‘goto’ as the ‘weapons person’.

Amongst that, there is the wider team working together to keep heading towards the same vision, communicating progress and changes which is incredibly hard. See the 🎬 Psychonauts 2 game development documentary as a first hand look at that.

On smaller teams, you have more hats on, so you can be jumping from one thing to another. For example, maybe one day you’d be working on a gameplay system, such as achievements or combat. But you may need to jump over to do something else that you’re capable of doing or have to do, like back-end work or tool development. And that can change quite rapidly throughout the development cycle, depending on the type of game it is.

For a pay-once game, you probably won’t be jumping that much since there is less to react to (eg. a publisher demo). But on a game with a long tail, like free-to-play, you may have to react to events or changes when the game is live. Content is delivered on a regular basis such as every 2 weeks and may have to react to changes/issues on a similar frequency. The daily active user count (DAU) may suddenly drop due to a recent content release or a platform and therefore you may have to switch gears to be able to react to it.

There’s variants of different monetisation models between those, such as where you pay once and you’ve got DLC after that. And there’s different concerns between each one, many different factors.

When you talk about the pay-once premium model, where the user buys a game once, you are kind of in a waterfall-type style development. Generally there’s a fixed date of where to get everything done by. There are almost fixed stages making the game, getting feedback as early as you can in the prototyping stage, going through a production stage, going through a bug fixing stage and then shipping it (broadling speaking).

And within that, you also have certain milestones you have to hit. I don’t know if it’s still the case these days, but back when I was working at EA, we would have different dates that we needed to hit for different platforms. They will have different lead times to test the game and see if it meets their minimum expectations. They would have something like a checklist saying that your game cannot take more than X seconds to load a level, it cannot be on a black screen for more than Y seconds, it cannot drop below X FPS and similar criteria.

And then you have to prioritise certain bugs and work on a per-platform basis to ensure that there’s a ‘final’ build in time. Eg. If Nintendo took the longest to test again the checklist, you would have to make sure that their build was ready first. And then when the platform holder gives the green light, you can go through the manufacturing process to burn the discs. Prior to that, you also had to deal with marketing material so they could print off the packaging of the game.

Funny story is that in one of the titles I’ve worked on, we actually didn’t realise that we put on the back of the game that there would be four mini-games. And we realised we only had three mini-games in the game very late in development 😱. So we had to scramble and invent a new mini-game as we couldn’t change the packaging. We managed to add one in over a weekend and while it wasn’t a bad mini-game, it was definitely rushed. Also, we were lucky to get the voice actors to come back and do some pick-up lines, which was great.

With a live game, then you’re in a different cycle altogether where there’s a continuous stream of smaller content released after the game’s been initially shipped. I think Candy Crush was on a two-week basis, or at least Farming Heroes Saga was. So you always have this cycle of, okay, we need to make new content, what new content are we going to do?, test, release, repeat. And then larger features such as events and new gameplay mechanics are done in the background across several content releases.

Because it’s a regular process cycle, there’s less pressure and the scope of the work is relatively small per release. It’s also quite forgiving as you can change and release things really quickly as well have the flexibility to push back certain features as it’s only two weeks till the next release. Unless you’ve got a fixed promotion, like Valentine’s Day, for example but even then, that would be planned and worked on ahead of time to account for some slippage/delay.

I personally prefer shorter cycles and constant releases to longer, ship once games. Mostly because you get to put your work in players hands sooner, get feedback and use that to improve the next release. I find that much more fun, engaging and immediate to work on compared to a multi-year development cycle.

Many hobbyist game developers create games out of passion without much of a business plan. But unfortunately, passion alone doesn’t pay the bills. When it comes to monetization, what are some things that you think game developers should do, and what pitfalls should they try to avoid?

We’ve had quite lively discussions about this on the Discord server about this and generally I usually find that people underestimate how much the monetization models can affect the game design. One of my controversial takes is that the monetization model tends to drive or affect how the game is designed from the early stages of development. So if someone is thinking about monetizing the game, the earlier they think about that, the better place they are to be able to think about what changes or what they need in their game to help support the monetization model.

Even for premium pay-once titles, just using back of the napkin maths you will have to consider the price print of the game and the platforms to target. Depending on how many copies are projected to sell based on the platform, genre, audience size and the target revenue, you can get a rough grasp on the price bracket the game needs to be in. Because there are expected ‘entertainment value’ for games within the price brackets, it would give an idea on how ‘big’ a game needs to fit that price bracket.

Inversely, if there was a fixed price bracket to target and a target revenue, it would give a sales figure to hit. And that would mean you have to ensure that the game design, genre, art style and other factors have the potential to find an audience of that size. There are exceptions to this as with anything with breakout hits (Amongst Us comes to mind) but there are a number of videos that talk about thinking about these processes and market research up front: 🎬 Know Your Market: Making Indie Games That Sell and 🎬 The Successful Paradox of Combining Business Strategy with Nonconforming Game Development.

And if we go to the other end of the spectrum with free-to-play, especially on mobile, the way to monetise is much more closer to retail:

If you go to any supermarket or department store, or any other shop where you can freely go in and exit, there’s a lot of ways that they utilise to try and have people come in and actually buy something. Product placement plays a huge role, where you can see this in places like IKEA, supermarkets, where you queue up to pay for the items that you want to buy. They always have these little things that people tend to want to have impulse buy items and tend to go, “Oh you know what, I’ll buy that because it’s there”.

There’ll be chocolates, chewing gum, tissue packs, hand sanitiser, all those little knickknacks in a lower price bracket. And because you’re in a situation where you can’t technically leave because you are in the queue, people tend to look at those and go, “you know what, I’ll take this and take this,” which is how they get their shoppers to buy that little bit extra.

This is the same thing you see in a standard midcore free-to-play games where they look for the best places in the game flow to prompt the user on purchasing something they may need or after a certain event. On top of which, data analytics with A/B tests play a huge role in finding those spots without a long term detriment of user experience and churn (where players leave the game).

It’s also been shown that, once a user buys anything, they are more likely to spend more as they’ve gone over the friction of using money, hence a lot of focus on that first purchase. This may include sales that advertise front/outside retail shops to entice shoppers into the store or first time user bundles in games that are only available once but include massive savings.

NaturalMotion’s CSR Racing 2 (Pocket Gamer)

This is also a useful article: IAP Packs in Mobile F2P: Analysis and Design.

With this in mind, the game design would have to have opportunities and meaning to the purchases as part of the core and game flow. Not doing so would make it feel forced and tacked on to the user.

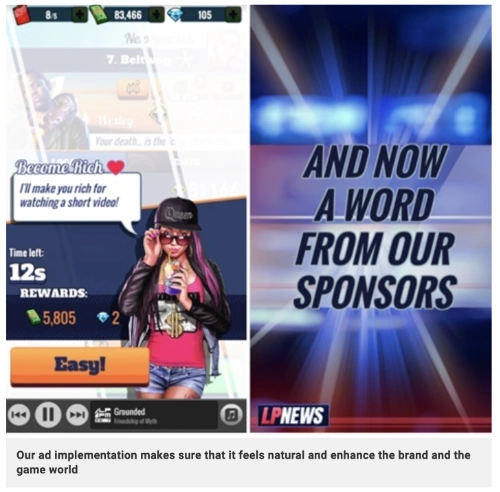

A great example and write-up on building monetisation into the game, is Fastlane from SpaceApe. A casual/mid core shoot ‘em up that focused on rewarded ads as the monetisation model. And with ads, you want to be able to get as many views as possible per user at the best eCPM rates (estimated revenue per 1000 impressions).

They wrote on how they integrated rewarded ads as part of lore and theming in game, the data analytics, the lead-up and the end of it, on how they did all these experiments, A/B tests, etc. All in order to get the best eCPM rates, as many ad views as possible without losing players.

The revenue went from $5K to $45K a day and is worth reading on Space Ape’s blog.

Unfortunately, people don’t like talking about the money side of things especially on the web where it’s mostly ad-driven. This is because people find that it feels like nickel and diming, or trying to squeeze extra value from the player, etc. And I understand that. There are many levels on how far to push and what people are comfortable or willing to do to earn money in this space.

To give an example of the thought process, let’s say we were developing a hyper casual game that is rewarded ad-driven and wanted to target $300 a day. According to the Appodeal 2023 report, the US audience is roughly $20 eCPM for rewarded video ads. That would mean to hit $300 a day, I would need 15,000 ad views ($300 / $20 * 1000 views). So that would mean I would need 5,000 DAU, watching 3 ads per daily session, 7,500 DAU watching 2 ads or some other combination.

So the game would have to have a ‘hook’ for multiple play sessions and hopefully keep players in the longer term. It would also need to ‘encourage’ players to want to watch the ads somehow that’s least intrusive to the game but still enticing enough to get those clicks. Then the problem compounds if we need more revenue or can’t keep that sustainable DAU number. What do we do? Forcibly add more ad view opportunities? Use paid user acquisition which adds to costs but gets more volume of users? etc.

Here’s two videos that show either end of that space that even if you don’t agree with, are worth watching to understand the space: 🎬 Dark Patterns: How Good UX Can Be Bad UX and 🎬 Let’s go whaling: Tricks for monetising mobile game players with free-to-play.

TLDR: Try and think about monetization as early as possible and how that can impact the game design.

(I haven’t touched upon other monetisation models here but should also be considered if you want to research more: subscription/battle passes, shareware and DLC. There’s also audio ads like AudioMob which I think is much less intrusive to the play experience).

What do you think the future of browser games is? Will WebGPU make a big difference in this ecosystem? What would be your predictions for the rest of 2023 and for the years to come?

WebGPU is an important milestone in allowing developers to make full use of the power of computers that browsers are on. It’s really exciting of the possibilities that it can bring once it becomes mainstream, similar to how WebXR has allowed developers to build and share AR/MR/VR content through the web. Currently, it feels like there’s no demand from players for it at the moment in terms of having really high fidelity AAA games running in the browser. It will be interesting to see how that may change when the initial wave of games/possibilities is released that really show off the capabilities.

I also think generally people underestimate what the browser is capable of doing today. People tend to think that web games are only capable of hyper-casual games that you see on the game portals where it’s simple, straightforward gameplay that players can quickly dip in, play and leave. But that’s mostly because that’s what does well in the current market in terms of getting players and revenue which is why developers keep making them. However, the current capability of browsers is so much more and game developers have done some really great work that many people are unaware of when it comes to discussions of web games.

On the PlayCanvas side we’ve got Kiloo, who are doing some fantastic looking, FPS-stylised games with fantastic character animation. Super Snappy looks very polished in terms of style and feel. Aritelia and Tribals.io show open world capabilities in the browser.

Then there is Hordes.io, a massive MMORPG game, Krunker.io, a hugely popular FPS, Duelyst, a polished collectible card game and many more.

Unfortunately, unless there’s an audience that wants or plays games like this in the browser, no one’s going to make games like it. Really, the problem I see that needs solving right now is discoverability and monetisation. This is in contrast to mobile or PC, where there’s established centralised, mainstream storefronts, such as Android Play Store, the Apple App Store, Steam, Humble Bundle, etc.

People know they can get games from these trusted stores so they keep using them and coming back to them. Mobile’s the best example here, where you can make a premium or a free-to-play game and as developer, you can point people to a store where they already have an account and their credit card set up. It’s lower friction to the user where it’s a literally one-touch or one-click payment for anything like in-app or premium purchases.

The mobile app store also deals with basic inventory, so you can do in-app purchases (IAP) and know if people have already purchased something and on top of that, there’s established ways of adding and managing features like subscriptions, ads, etc. They don’t really have any gatekeeping as well. For the most part, a developer can pay a small fee and as long as you go through the review process and it doesn’t break any of the (quite frankly) lax rules, anyone can put the game on the stores.

This is what we’re missing on the web, where we have the decentralised part. Anyone can put up a game on the web but discovery is hard. If you wanted to do IAP, you would have to create your own store, handle payments etc. and hope that the player trusts the site enough to use it. So most games on the web default to ad driven revenue which is much simpler, but limits the games that fit that monetisation model as I talked about earlier.

I would like to see a service that becomes the de facto standard for single sign-on, purchasing, and inventory for web games. That would be fantastic. The closest we’ve had to this and something I’m keeping an eye on, is probably Discord. Most gamers are likely to have a Discord account and they’ve recently announced Server Subscriptions where server owners could earn revenue through their communities. Using Discord for the single sign on and to use to gate content based on subscription/battle pass model could be an interesting path to go down. Especially if doing certain things on the Discord server could affect the game and visa versa. I can imagine it being the closest to a one-click login, one-click payment service right now.

I also expect to see more platforms like WebGamer.io come up out of the ashes of the portals that have been closed down (Snap Minis, Miniclip, Kongregate, etc). Some I know about are under NDA so won’t risk mentioning them here 🤔. But ones that have caught my eye are HypeHype, a TikTok style feed of games that are playable in app made by users that other users can fork and remix, also directly in the app. And there’s dot big bang which is Roblox/Garry’s Mod style games development, playable in a browser.

Very exciting stuff around the corner and expect to see more of this over the next year.

What are your thoughts on using the web stack (JavaScript) to publish games to Steam and mobile stores (packaged with Electron or PWABuilder, for instance) instead of native engines like Unity?

My general approach when choosing the tools is to always use the best tool that suits the job. However, the ‘best’ tool is relative to this situation depending on the developer, team and needs for the game.

It’s rather difficult to argue for using JavaScript or web stack for developing native games on Steam and mobile stores unless the game is already in a web format, or if there are plans to develop a web version in the future. If I was making a game and the primary platform was going to be web-based, I would likely use a WebGL-based JavaScript engine and stack. Afterwards, I could put it onto platforms like Steam and mobile stores to increase my revenue or user base.

However, when it comes to using broader tools like Unreal and Unity, it’s hard to argue against them, especially for mobile gaming. If I were making a game for a mobile platform, I tend to lean towards using Unity since the monetization, integrating in-app purchases, and other major libraries are already built into it. With the extensions built up for you, you will find it easier to get started right out of the gate. On top of that, you can expect to get better performance and save more battery life on users’ devices.

The counter to this is if I already have experience and knowledge to build games with a web stack, depending on the needs and timeframe, there’s an argument it would be ‘best’ to use a native web wrapper. Especially if it speeds up the time to market and helps validate the market for the game and can later be ported to a native engine later down the line.

Let’s now switch the focus to your experience working with PlayCanvas. Could you explain what PlayCanvas is for people unfamiliar with it?

As a ‘one liner’: PlayCanvas is a WebGL engine and editing platform, which allows you to build and run rich, interactive experiences directly in the browser or webview. No install needed.

It’s a web-first engine which means that it is very much focused on using the web to the fullest. This includes embracing open standards such as WebXR for AR and VR experiences and supporting the glTF Standard for models and materials. The engine runtime is open source under the very permissive MIT licence. It’s a completely open box and has had developers contribute features/fixes over the years.

If you’ve used other games engines, then the Editor will also look familiar to you too. It’s a collaborative online Editor where multiple users can build experiences visually. Add models, update textures, modify materials, setup animations, write code, publish and download builds through the browser.

There is a public roadmap on GitHub with estimate/target dates for issues.

See what people have made with PlayCanvas and also the feature list on the site 😄.

Some of the most impressive HTML5 games I’ve seen are made with PlayCanvas. Which ones are your personal favorites?

Ooo, my favourite is probably the Kiloo series of FPS. Especially Warbands and Fields of Fury due to the stylised look and amount of work they did for character animations. It looks and feels really polished because of that.

Outside of PlayCanvas, I’m super impressed by Hordes.io, it looks fantastic and has done incredibly well on the market showing that audiences for ‘deeper’ browser games exist! We need more like this to help shift the market.

What is your opinion on building games using 2D/3D libraries like Three.js or Pixi over more full-featured engines like PlayCanvas or Babylon.js?

It depends on what you want to work on and what you’re trying to build. If you’re looking for something relatively lightweight and you’re happy to build up the systems to do things like asset loading, game loops, features systems yourself, go for it! Some people are very happy to take framework libraries and build features and tools on top of it because they have their own philosophy or direction of what they want to build. Rogue Engine is a great example of someone taking Three.js and adding their own game engine features and tools on top of it.

There can be some sigma about not using a game engine and writing/building from scratch in the sense of spending time building something that already exists. The classic Just use Unity/Unreal response comes to mind on many game dev servers which is a bit of a shame, especially when there’s a lot that can be learned and achieved by rolling your own engine and systems. Especially, if the game or developers have specific needs.

For example, the game Wargroove created Halley, a lightweight C++ 2D games engine. The developers built their own engine pretty much from scratch because they decided that they didn’t need an engine like Unity. Where they would have to take a small part of it and try to work around it the rest. They wanted to write something that was bespoke for their game or the game style and therefore have much higher control over what they need, what they don’t need and design it in a way that fits their development processes better.

On the other side, there are developers who want to focus on the game itself as much as possible. And they want the immediacy to build that quickly which game engines can give them. With PlayCanvas especially, a developer can get started really quickly as no install is needed and the tools are directly accessible in the browser.

It’s something I will show in a 2-hour workshop, building a small game with PlayCanvas at JSNation on 9th June.

Finally (and I guess this question is now a tradition for Web Game Dev interviews!), what advice would you like to give to aspiring game developers?

In general, I would say make stuff, show your work, finish it, review what you’ve done, learn from it, and repeat. Continue to create new things and try different frameworks, libraries, and technologies. Start small and build on top of or create something different, trying different methods or building on existing projects and drawing inspiration from other developers and work.

It doesn’t matter where you get started; go where your interests take you. If you’re interested in writing a game engine, do it, even though it goes against common advice. Creating a simple game engine can teach you a lot, including what the difficulties are in doing so and why developers favour engines over frameworks and visa versa. There isn’t one right way to start; getting started and creating something is more important as it keeps you engaged and interested.

For those new to game development, I generally recommend using GDevelop. It’s an excellent entry-level tool where you can start putting together a 2D game without writing code using the event-based codeless option. It’s quick to get something working, playable, and shareable with people. Later, you can JavaScript code for more bespoke logic, making it a great way to ease into game development, programming, and design.

When I started, I used a program called Games Factory, a PC games engine by Clickteam in the 90s. It also had a codeless option, so I started making simple games and built on that. We shared games using floppy disks with friends at school, and it was fun. It didn’t matter whether it was good or not; I enjoyed it, and my friends too!

Then I started University, learning other tools like 3D Studio Max, Q3 Radiant, C++, OpenGL and SDL. For my final year project, I looked at making games for the GBA with a friend. We found out that you could make games for the GBA using a homebrew SDK and playing them via emulator or flash carts. They had a big homebrew community back then and made it easy to get started. The community released libraries, documentation and tools to help make games on the GBA and were very active in helping each other on the forum.

The game wasn’t very good as we spent a lot of time just trying to get something working and rendering correctly on the device. But it was a huge learning experience as it was such a departure from PC development. I was super happy when I found a way to make the radar in the top right by using the collision data and writing directly into the sprite data.

Now game development is much more mainstream and it’s never been easier to start making games. There’s a huge range (maybe too huge?) of tools that are available for free. Want to make Gameboy games? There’s now GB Studio, a visual based tool that produces builds playable on device! It doesn’t matter what people choose to get started as long as they get started. Read and learn as much as you can along the way.

For example, there’s a great channel by Masahiro Sakurai the creator of Kirby, who has fantastic, concise videos covering high-level game development principles. Very approachable for anyone new to games development. Riot Games has a Game Design Curriculum designed for educators to run workshops in games development.

Also learn and draw inspiration from outside of games. There’s a great book on design that I recommend to everyone called ‘The Design of Everyday Things’. It deals with the design and user experience of physical products, such as door handles, light switches etc and how over time.

TLDR, if you’re interested in games development, find a tool that looks good to you and get started, read and learn as much as you can and talk to communities. You never know where it might lead you. The use of games technology is now everywhere including TV and film, space exploration, architecture and more!

Thank you so much Steven for sharing your story and thoughts on the web game ecosystem! Go give Steven a follow on Twitter or LinkedIn and share this interview if you liked it! ❤️